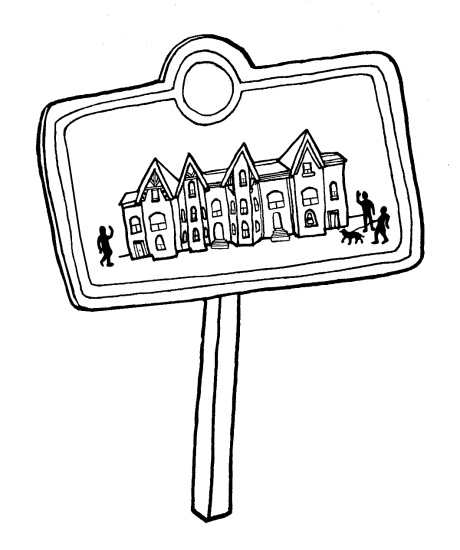

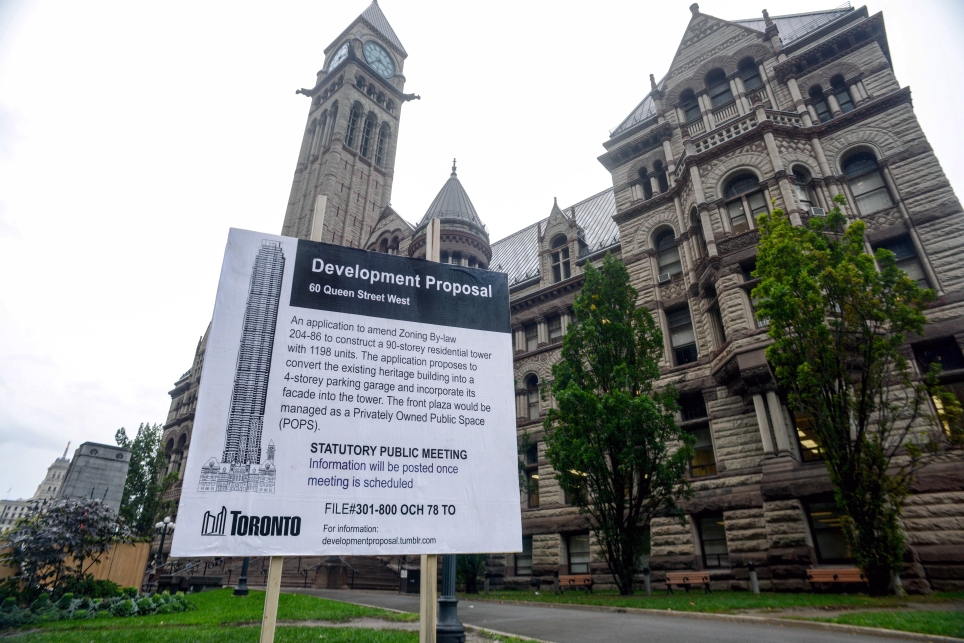

In late October, Glo’erm and I put up a fake development proposal sign on the lawn of Old City Hall in Toronto. The proposal included a 90-storey residential tower, while the heritage building would be converted into a parking garage. At the bottom of the sign was a link to a website that featured several other, increasingly absurd, parody proposals.

I guess pranking is still in style, because the stunt was covered by every local news outlet in Toronto, with many thinking it was real. The project struck a chord with a city anxious about how fast it is changing.

Some of the comments on CityTV’s coverage of the story, ranging from outrage to… outrage

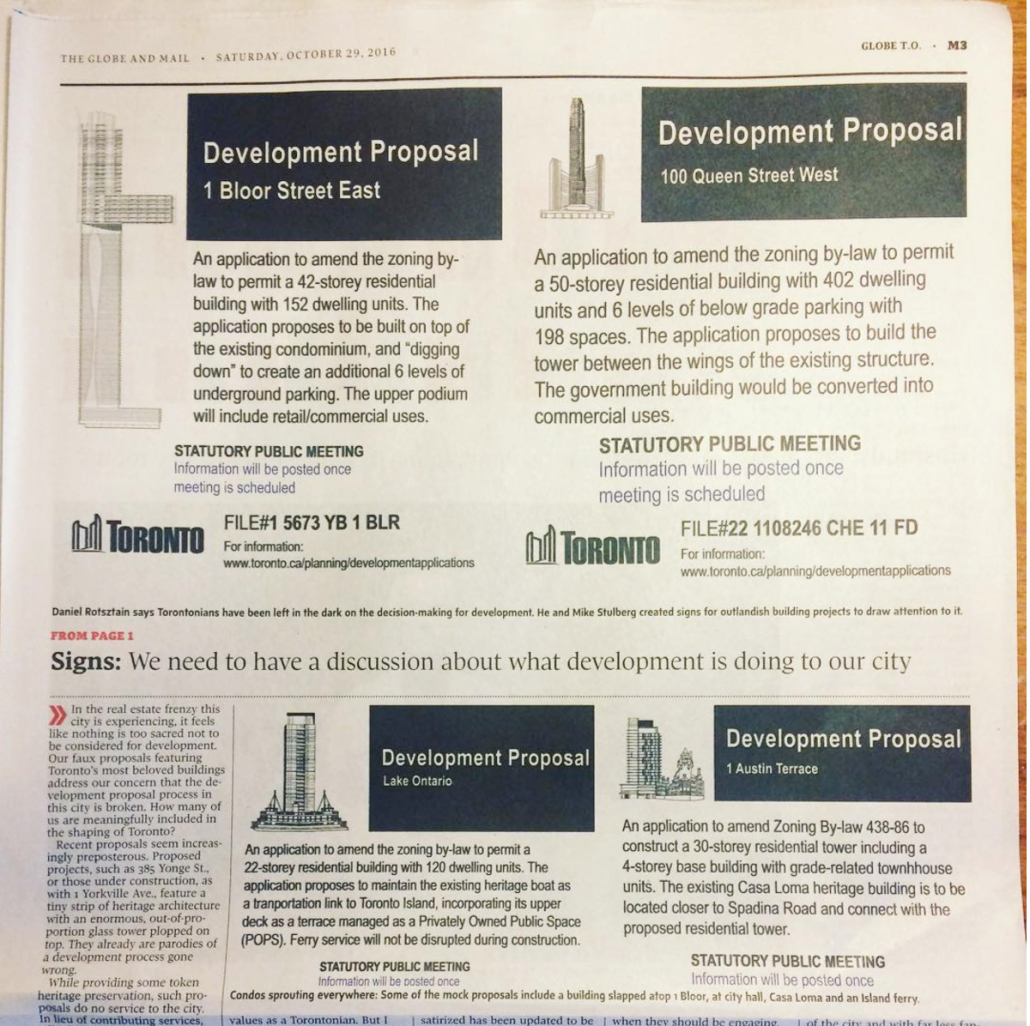

After articles in blogTO, the Toronto Star, Metro Toronto, and Canadian Art, and some hilarious TV news coverage where they created animations of the proposed buildings actually coming out of the existing structures, I wrote about our motivations in the Globe and Mail. (We were initially anonymous, but decided to reveal ourselves to explain the ideas behind the project and keep the conversation going, not to mention some good press).

The signs in the print edition of the Globe and Mail, October 29, 2016

As soon as the article was published, there was a vast amount of criticism regarding my position. One critic called it “NIMBYism dressed up as art”, despite my very clear stance that development is needed, but that doesn’t mean it has to be so extreme and uncontrolled. I do agree with most of the critiques, and my knowledge about the state of development in Toronto has expanded greatly from this experience.

Basically, the reason we’re getting so much “hyper-density” in Toronto, is because of what is known as the Yellow Belt – huge swaths of Toronto zoned as Neighbourhoods, and protected from development that doesn’t meet the character of the area. This means that people can use the official plan to reject even gentle, mid-rise density from these neighbourhoods. With a rapidly growing population in Toronto, that density has to go somewhere – and its landing in neighbourhoods where there weren’t many previous residents to defend them, like along lower Yonge Street and Liberty Village. One planner described it as a stress ball: if you squeeze the ball, all the pressure has to go somewhere, and it’s popping up as a extremely high density in certain parts of the city.

I was able to express a more nuanced view in an interview with NOW magazine.

Inclusivity is important: Toronto has an affordable housing crisis, and its important to increase the supply of housing so that the city remains accessible to all. The development proposals we are critiquing are not the answer: they are not affordable, and their extreme heights do not contribute to a higher quality of life.

I stand by our initial critique of an opaque proposal process that leaves most Torontonians out of the decision making process. When you go to a public meeting regarding a development proposal, that meeting is only accessible to a certain segment of the population, who have the time and knowledge to be able to respond to a fully formed proposal that will probably be built. At those meetings, as critical urbanist Jay Pitter has said more than once, the most important question is who is not at those meetings, and why aren’t they there?

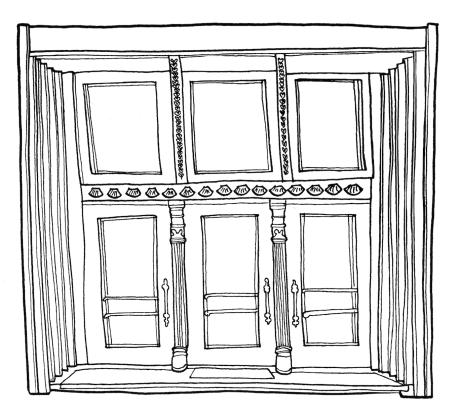

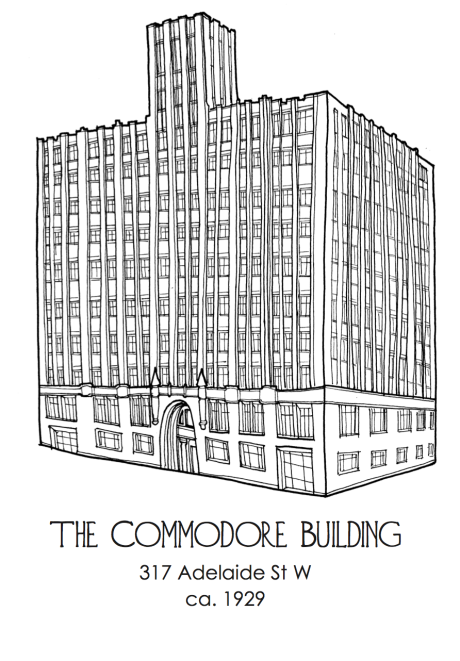

My illustration of the Commodore Building on Adelaide. Unlike Benjamin Brown, I didn’t use a ruler!

My illustration of the Commodore Building on Adelaide. Unlike Benjamin Brown, I didn’t use a ruler!