WexPOPS is a pilot of the plazaPOPS project, an initiative spearheaded by Daniel Rotsztain, aka The Urban Geographer, and Brendan Stewart (OALA, CAHP), professor of landscape architecture at the University of Guelph, and former Associate at ERA Architects.

In an interview supporting his recent book Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure can help fight Inequality, Polarization and the Decline of Civic Life, NYU sociologist Eric Klinenberg points to an idea that many urbanists take for granted, but that the general public may not: “[T]he social life we experience doesn’t exist in a vacuum; there’s a context for it. It can be supported or undermined by the places where we spend time.” In other words, there is a relationship between the design of our physical environment, and the social life it enables, or not.

Klinenberg urges his readers to think about the types of places that foster connections and relationships between people and that build strong communities not as nice to haves, but rather as an essential infrastructure that buttresses the foundations of democracy, inoculating society from many of the challenges that define our current moment. He argues that “social infrastructure” will only become more critical as communities are forced to adapt to the challenges associated with climate change.

Closer to home, the Evergreen Foundation’s Towards a Civic Commons Strategy proposes a similar vision for “a network of public places and facilities that enable communities to learn, celebrate, express collective actions, collaborate and flourish, together.”

Inspired in part by these ideas, we’ve been working for over a year on an experiment to test the potential of creating a type of civic commons/social infrastructure within the ubiquitous strip mall parking lots that define the main streets of post-war neighbourhoods across the country, and which are home to millions of Canadians.

Open from July 5th to August 17th at the iconic Wexford Plaza at Lawrence Avenue East and Warden Avenue in Scarborough, WexPOPS is the result of more than a year of community consultations, planning and design work, and a collaboration involving 19 Master’s of Landscape Architecture (MLA) students from the University of Guelph, graduate business and planning students from the University of Toronto’s Rotman CityLAB fellowship program, a 15-member local working group, and a partnership with the Wexford Heights BIA.

The City of Toronto’s Public Realm Unit, Scarborough Arts, the TRCA, the Arab Community Centre of Toronto, Mural Roots, the Working Women Community Centre and a number of local businesses who supported the initiative in various ways, including the Kirakou family, who own the Wexford Restaurant and the entire plaza and generously hosted the project.

Funded by Parks People’s Public Space Incubator Grant, generously supported by Ken and Eti Greenberg and the Balsam Foundation, as well as the City of Toronto’s BIA Kickstarter Fund, WexPOPS proposes a big idea: to test the viability of exchanging parking spots for a community gathering space all on private commercial property. It’s a new take on POPS — privately owned public space — and experiments with the city building potential that commercial business owners can exercise by enhancing community life in the neighbourhoods they serve. Hopefully, they’ll also seeing an uptick in business.

Similar strip malls are found throughout Toronto’s inner suburbs and in post-war neighbourhoods all over Ontario and Canada. In many cases, especially in Toronto, the retail remains vibrant and local, serving as important settings for community life, and features numerous restaurants and shops serving food and offering goods from all over the world. The Wexford Heights BIA, a two-kilometre strip running between Victoria Park and Birchmount along Lawrence Avenue East, features over 60 restaurants, and has been celebrated by food columnists as a major dining destination.

The project grew out of Daniel’s fascination with the strip malls he frequented in his youth, culminating in his 2018 MLA thesis at University of Guelph, which was overseen by Dr. Karen Landman and Brendan Stewart. It builds on Daniel’s work as an artist, examining the setting of Toronto’s public life, including All the Libraries Toronto, his documentation of all 100 public library branches in the city, as well as a recent residency at Yorkdale Mall that asserted the centrality of private shopping centres in Toronto’s social geography.

WexPOPS also builds on Brendan’s citizen engagement Tower Renewal work with ERA Architects, including parking lot to community space conversion projects at the East Scarborough Storefront (2010 – 2015) and Ridgeway Community Courts (2015-2017) in Mississauga.

The final design of WexPOPS features a series of modular planters, benches, tables and umbrellas, all clad in marine plywood and trimmed in cedar. Occupying ten parking spaces, the installation creates a comfortable and sheltered ‘room’ in the middle of the parking lot, and frames dynamic views of the strip mall behind. The carpentry was done by Guelph-based Ben O’Hara Design, and all of the components were designed as modules that could be re-configured into different arrangements to suit various future site conditions, and also to flat-pack for easy assembly and storage.

Six design concepts for the project were developed through a series of community workshops by student teams in a graduate community design studio at the U of G this past winter, and the ideas most favoured by the working group and a wider online engagement were incorporated into the final design. For example, one student team developed the colour scheme for the project, which includes vibrant red, orange and yellow and was inspired by the spice markets of the Middle East. Another student team proposed a space of lush and immersive greenery, an idea that resonated in the community and which dominates the final design.

In all, WexPOPS features over 500 plants, which are planted in colour-coded pots: red denoting native perennial wildflowers and grasses, orange for annuals, and yellow for edibles. The pots were created from salvaged recycling pails from the university, and were painted and drilled for drainage. The annuals and edibles were grown in campus greenhouses and donated to the project. All of the native plants, grown by Native Plants in Claremont, will be donated to the Toronto Region Conservation Authority, to be planted in a local stretch of the Meadoway this fall.

Twelve local youth from an after-school program run from the Arab Community Centre of Toronto across the street have been hired as site supervisors, stewarding the site through daily watering, waste management and other set-up tasks.

At night, LED lighting within the benches creates a welcoming atmosphere, and the illuminated strip mall signage creates a dynamic backdrop. During several evenings this summer, including an upcoming event on August 17th, the WexPOPS stage (with a mural designed by Echo Railton and painted by community volunteers) offers music and dance performances by local artists, co-curated by Scarborough Arts as well as urban ecology workshops lead by the TRCA.

WexPOPS is meant to be a hub of social activity for the local community, but also to attract visitors from beyond — a desire articulated by our working group, whose members wanted to `put Wexford on the map.’ The space features a neighbourhood business directory which encourages people to patronize the local restaurants and businesses (and eat takeout in the space), as well as a ‘dot map,’ which prompts visitors to place a sticker on a map showing where they live. This data will help the team evaluate the impact and reach of the project. The signs were donated in kind by CAS Signs Company, a printer located in Wexford Plaza a few stores down from WexPOPS. The ‘Wexford Wish Tree,’ inspired by the shape of the sumac and CNC milled by local AC Waterjet, poses a different question every two weeks and invites visitors to write their answers on a horticultural tag and tie them to the tree for others to read.

WexPOPS may be popping down after August 18, but the proof of concept has already inspired many to reconsider the potential of privately-owned strip mall parking lots as community gathering places, including, perhaps most importantly, the Kirakou family — the property owners and our project hosts. To more concretely determine the project’s impact, the plazaPOPS team is conducting a public life study, modeled on methodologies pioneered by Denmark’s Gehl Architects. We are also studying the impact on parking and local business activity. The Rotman students, guided by Prof. Rafael Gomez, prepared a background study that informed the research design.

Project findings will be published later this year in an exit report, but already, many working in the urban design, community arts, and economic development sectors have noted the potential for applying the plazaPOPS concept beyond Wexford Heights, understanding the value of creating space to support the social life of communities in strip malls across Toronto, Ontario, and Canada.

photos courtesy of Rotsztain and Stewart

More information about the project and its design and planning process are available at www.plazaPOPS.ca and via twitter and Instagram at @plaza_pops. You can reach the team at plazapops@gmail.com.

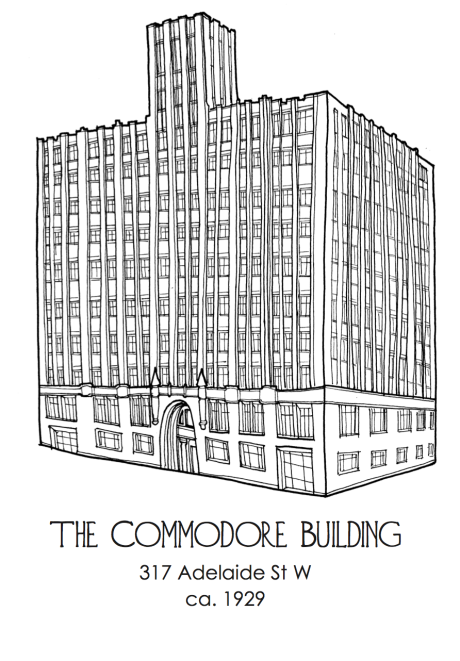

My illustration of the Commodore Building on Adelaide. Unlike Benjamin Brown, I didn’t use a ruler!

My illustration of the Commodore Building on Adelaide. Unlike Benjamin Brown, I didn’t use a ruler!