This reflection is cross-posted on the SLU Urban Readings group. According to SLU, “Urban Readings connects a small team of chroniclers across the hemisphere with the mission to spot and comment on relevant articles connected to the urban realm in international press. The group of writers consists of academics from various fields intersecting the urban, with insight in current discussions from around the world.” Check out more readings here.

The COVID-19 lockdown hit Toronto like the eye of a hurricane. While the virus was causing chaos for our ill-prepared healthcare system and brought the economy to a precarious standstill, it all felt strangely still on the streets. An eerie calm descended on Toronto as cars evaporated from the city’s typically clogged roads and highways, the sudden lack of motors revving and cars whooshing created a deafening quietness.

Many were quick to see that the empty roads offered an opportunity to create a larger pedestrian realm so people could navigate the city while maintaining safe distances from one another to prevent the spread of COVID-19. After several weeks of advocacy for Toronto to open lanes of traffic to pedestrians, politicians and public health officials remained reluctant to do so, perpetuating a car-oriented logic that defines the planning and management of most North American cities. While cities around the world — including many in Canada — were opening hundreds of kilometres of empty streets to pedestrians, Toronto remained stubborn on the status quo. While advocacy was reaching a fever pitch amongst urbanists online, it had yet to pierce the mainstream discourse.

I am a member of the Toronto Public Space Committee and an organizer of its Art Subcommittee, exploring how we can use art to advance public space advocacy. At a virtual meeting, we realized that our collective effort to create more space for pedestrians in Toronto during COVID-19 and beyond needed something to rally around (and of course, a hash tag.)

The Social Distance Machine

With the help of artist and musician Bobby Gadda, we created the Social Distance Machine, a giant wearable hoop made out of plastic conduit piping and bicycle inner tubs to clearly demonstrate how large 2m really is — the recommended distance to stay apart to prevent the spread of COVID-19 — and how little space in Toronto is allocated to pedestrians to maintain that distance from others. We wanted to create a video that was humorous and highly shareable, to contribute a lighter tone to a very serious conversation. We released the video the morning of April 13 with #streets4peopleTO and by the end the day it had gone viral around the world, resonating with other cities that were facing similar struggles as they demanded more space for pedestrians to navigate their streets safely.

Toronto’s politicians and public health officials responded slowly. Despite endorsements from major thought leaders and an editorial from the Globe and Mail, the City of Toronto remained reluctant to accept the new reality that people were going to be going outside, and that the city’s infrastructure had to be adapted to facilitate pedestrian movement safely.

We Are Not “All in This Together”

A common phrase we’ve heard during COVID-19 is that “we’re all in this together”. The message is everywhere: posted in shop windows, on social media, in advertisements, and endlessly repeated in politicians’ speeches. The immense gap between those who have the time, space, and resources to safely navigate the pandemic and those that do not demonstrates that this catchy phrase is far from the truth. COVID-19 has emphasized the inequities and issues that existed before the pandemic, rendering them unignorable. As Paul Taylor, the Executive Director of Foodshare, a food security organization in Toronto, wrote in an op-ed to the Toronto Star, “many of the requirements necessary to ensure that we shelter in place are based on the belief that everyone has a smart phone with a generous data plan, ready access to computers and wi-fi, a car, and a credit card”. According to Taylor, the pandemic has most profoundly affected “the millions who were food insecure before the virus hit”.

In terms of urban design, COVID-19 has emphasized pre-existing mobility inequities including the ability to navigate the city safely. In a recent article in Spacing Magazine, Tricia Wood, a professor of Geography at York University writes that “mobility is everything in a city”. According to Wood, “the more freedom of movement you have, the more privilege and advantage you have”. Freedom of movement includes the speed you can get from A to B, access to physical resources and social infrastructure, safe ways of getting around, and safe places to dwell. Before the pandemic, mobility was often limited for those who are disabled, racialized, homeless and queer. COVID-19 has emphasized these pre-existing inequities, while the wider population has begun to understand what restricted mobility feels like.

While the Social Distance Machine went viral and contributed to advocacy for more pedestrian infrastructure during COVID-19, it failed to address the unequal experience of mobility throughout Toronto’s disparate communities and geographies. The Social Distance Machine video demonstrated the inability to navigate Toronto’s central sidewalks safely, but it overlooked what author and placemaker Jay Pitter has termed “forgotten density” in a recent essay in Azure Magazine. Urging us to look beyond the overly studied city centre, forgotten density includes tent cities, suburban social housing, shelters, favelas, temporary foreign worker dormitories, Indigenous reserves, and prisons. Forgotten densities are contrasted to what Pitter calls “dominant density”, which are “designed by and for predominately white, middle-class urban dwellers living in high-priced condominiums within or adjacent to the city’s downtown core.” According to Pitter, these “myopic, privileged framework[s]” of density refuse to distinguish between good density and bad density, failing acknowledge how income, race and disability effect our experiences of urban space.

Within these forgotten densities, residents “are scared to leave their apartments for essential reasons because they can’t practice social distancing in cramped entranceways, elevators and laundry rooms.” Vulnerable populations are at more risk in small apartments without enough space to quarantine, and so-called “front line workers” such as those employed at factories and grocery stores cannot afford to quarantine at home. They are thus more likely to be exposed to COVID-19 than those that have the ability to work from home.

Due to the majority of the population working from home, the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) has seen a 75% drop in ridership. Sean Marshall, an active transportation advocate and geographer, recently mapped the bus routes that remain crowded during COVID-19 for Spacing Magazine. He found that the bus routes that connect low-income neighbourhoods to factories in Toronto’s northwest remain overly crowded, preventing riders from practicing safe social distancing.

Advocacy for more pedestrian infrastructure requires the equity lens advocated by Wood, Pitter, and Marshall. According to Stefan Novakovic, the online editor of Azure magazine, “progressive urban advocacy means more than wider sidewalks”.

More than Wider Sidewalks

After several weeks of advocacy for more pedestrian space during COVID-19, the Mayor of Toronto announced on May 6, 2020, that the city would be opening 50km of streets to pedestrians, while fast-tracking the construction of new bicycle lanes. It remains to be seen where and how these pedestrian streets will be implemented. Using an equity lens, advocates need to ensure a geographically equitable distribution of open streets, ensuring relief is given to people most in need of space to navigate safely.

In New York City, more than 100km of streets have been open to pedestrians in response to COVID-19. According to writer Yessenia Funes in Gizmodo, much of those road closures are within and beside existing parks, with wealthier, whiter communities living nearby. As Funes bluntly puts it: “What about the people who don’t live near parks?” Advocates for more pedestrian space in Toronto and beyond need to ask the same questions as their cities pedestrianize roads in response to the pandemic.

Novakovic acknowledges that advocacy for pedestrianizing streets must include communities outside of Toronto’s downtown core. In line with Pitter’s assertion that we must include forgotten densities as we push for conditions for safe physical distancing, Novakovic identifies specific actions, for example the “immediate funding for elevator repair and building maintenance is needed for the city’s chronically underfunded social housing communities”. Toronto’s social housing has $1.6 billion repair back log; we can pivot from the urgency of COVID-19 to address this long-standing issue. As activists, urbanists, architects, and planners call for more pedestrian spaces in the wake of COVID-19, Novakovic urges that “it must be matched by an equally strong push for urbanism at the margins – and creating space for forgotten communities as city builders”. This assertion of equitable urbanism and mobility must be addressed throughout COVID-19 and and in the new post-pandemic world.

COVID-19 may have exposed the inequities that have always existed in our society. However, it also offers an opportunity for meaningful adjustments to our policies and advocacy moving forward. According to Paul Taylor, the pandemic “has given us an opportunity to reflect on what a just and equitable society could look like, one that is measured by how well it takes care of its most disenfranchised members.”

The Social Distance Machine, a giant wearable hoop made out of plastic conduit piping and bicycle inner tubes to clearly demonstrate how large 2m really is.

Sources:

Funes, Yessenia. “New York City Plan to Close Streets Is Weak As Hell”, in Gizmodo, May 2, 2020

Marshall, Sean. “Mapping TTC Crowding during a Pandemic”, in Spacing Magazine, April 1, 2020

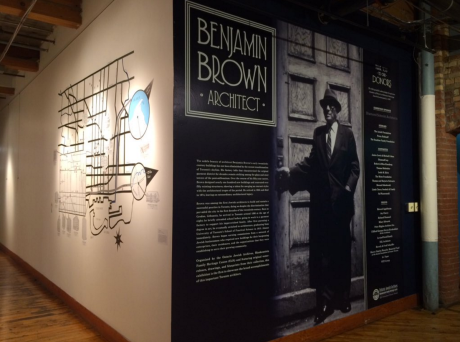

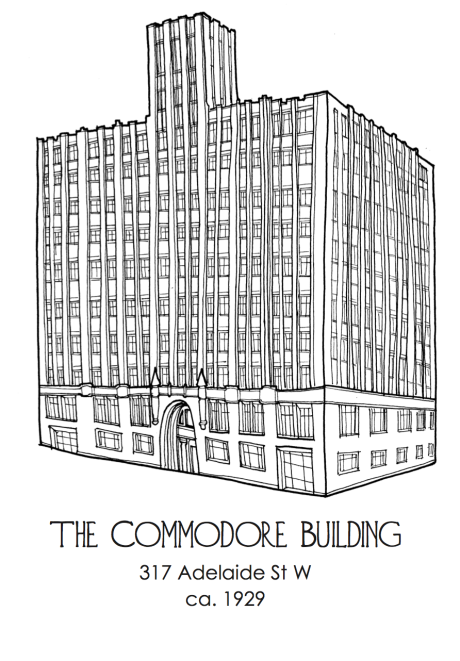

My illustration of the Commodore Building on Adelaide. Unlike Benjamin Brown, I didn’t use a ruler!

My illustration of the Commodore Building on Adelaide. Unlike Benjamin Brown, I didn’t use a ruler!