This post first appeared on the Koffler Gallery’s K-Blog, and was collaboratively written by myself, Mary Anderson, Mariah Hamilton and Jessica Dargo-Caplan. All photos by Mary Anderson.

On Sunday, May 3, 2015, the Koffler Gallery organized its first Jane’s Walk, which explored the Urban Legends of our West Queen West neighbourhood. Our walk was created and led by Urban Geographer and artist, Daniel Rotsztain.

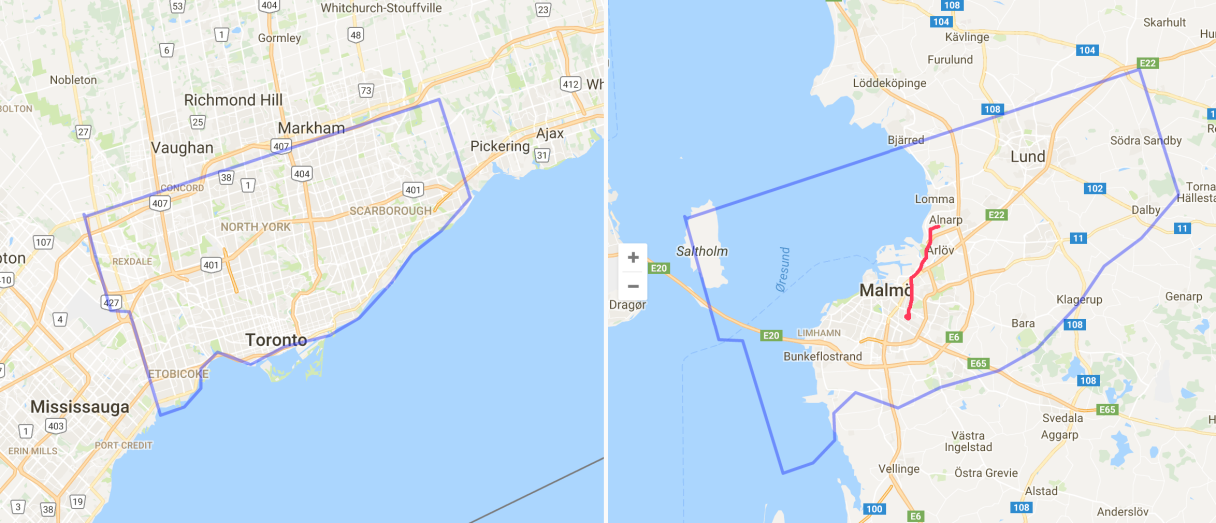

Inspired by the Koffler Gallery exhibition Erratics, (which explores the tensions between memory and fiction), Daniel introduced the walk by posing the question, “does Toronto have amnesia?”

Daniel led our group on a 2-hour walk through Toronto’s West Queen West neighbourhood, attempting to reassemble the neighbourhood’s memory by uncovering its histories, urban legends, and everything in between.

“What happens to a city’s notion of history when it has amnesia? A funny thing happens where the lines blur between fact and fiction. Without a strong historical tradition, urban legends emerge to fill the gaps and pass for that history. Strange historical blips, and anecdotal evidence emerge as what we remember. There are zones with strong historical memory, and others that people pass without a thought. But can’t we say that about all history? What distinguishes an urban legend – a story passed down through an oral tradition, from the random facts that become enshrined as historical evidence?” – Daniel Rotsztain

Our second stop was in front of The Lakeview Diner, where Daniel told us about the legend of the Lake Ontario Sea Serpent, which was named Gaasynedietha by First Nations people.

Our third stop was at Crawford and Dundas – where we explored the mystery of the green posts. Are they some sort of escape exits? Super Mario pipe replicas? Or are they berating tubes for a community of mole people, dwelling beneath Toronto? As Daniel explored these urban legends, he pointed out that the posts are actually ventilation stacks for a complex sewer system known as the Mid-Toronto Interceptor.

Our fourth stop was on Crawford Street – the buried bridges of Garrison Creek. Here, we explored the the legends of Garrison Creek, Toronto’s most famous lost waterway, as well as some lesser known facts about the creek including lost visions for its future.

Did you know that you used to be able to navigate the creek by boat, well north of Bloor, and that it was 10 metres wide and 20 metres deep at its largest?

Our next stop led us through the paths of Trinity Bellwoods to the park’s valley, or what it has become affectionately known as the Dog Bowl.

We often hear that Garrison Creek is “dead” or “lost” – but is it really? Here Daniel described some of the legends of Toronto’s zombie rivers, rising from the dead. These lost and buried rivers make themselves known quite frequently – re-emerging during rainstorms and leaching ancient dump chemicals into waterways. “The creek is not dead, but was buried alive!”

We continued our walk through the rest of Trinity Bellwoods to stop at our next location, the Trinity Gates. Just as the topography leave clues of lost rivers, Trinity Bellwoods’ gates are a clue of lost campuses. Here we explored the legends surrounding Trinity College, and other architectural fragments.

On CAMH’s grounds we recalled the history of the provincial mental health institution, and how the original 1850 buildings were demolished, leaving only its walls. Here we also discussed the legend of failed architecture, and the truth of failed governance.

Our next stop was at Dovercourt and Sudbury Streets where we remembered 48 Abell Street – an important building for West Queen West’s early art scene. It has since been demolished and replaced by condos.

We concluded our walk at Queen and Dovercourt, in front of West Queen West’s iconic, You’ve Changed mural. Daniel invited Carrie Lester to lead this portion of the walk. Carrie is a Haudenosaunee storyteller who told us about the meaning of Toronto, the myths and history of the land on which the modern city is built.

The walk brought to light many kinds of urban legends and histories. Stories were told as we attempted to untangle fact from fiction, and knit together our collective histories.