Guest post by Natalie Logan, a documentarian, artist, and aspiring urban geographer

What’s the difference between the woods and a forest? Scale. Then how relevant that the area south of Cedarvale and west of Forest Hill is called “The Woods”?

Most people know this area as Humewood but there is something more poetic with the vagueness of calling it The Woods and dropping the specificness the prefix “Hume” creates. Think of other areas of Toronto that conjure up that kind of feeling, like The Island or The Beaches (though, apparently locals call it The Beach, and technically The Island is really a bunch of islands).

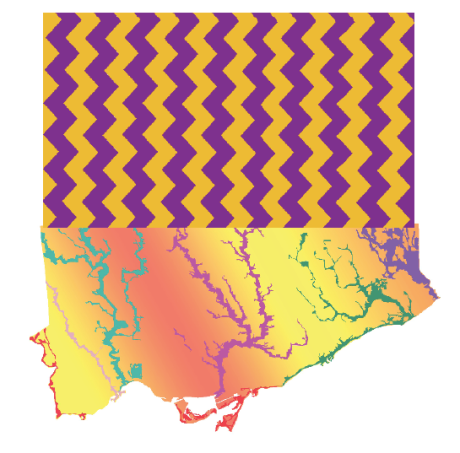

Insiders call their area The Woods because they are familiar with its street names. From the east to west you have Kenwood, Wychwood, Pinewood, Humewood, Cherrywood and from the south to north you have Wellwood, Maplewood, Valewood. According to the Wikipedia article the given boundaries are Bathurst Street on the east, Eglinton Avenue to the north, Arlington Avenue to the west, and St. Clair Avenue to the south.

I grew up in the “epicentre” of The Woods. At least a decade of my childhood happened at 24 Pinewood Ave and I currently live off of Wychwood Ave. So I think I have some credibility here. I would expand the boundaries of this area to extend south of St. Clair to the bottom of Davenport because of the Wychwood barns and Wychwood Park, and I would also expand the boundaries as far west as the most recognizable wood named street in the area, Oakwood Avenue. Why leave Oakwood out? Arlington is such a puny side street by comparison and all the other streets that make up the official boundaries are major.

What is interesting about the Wikipedia article on The Woods isn’t just that it challenged my understanding of the boundaries of my neighbourhood, but also the comparison it made between the wealth of the surrounding neighbourhoods. It pits “wealthy Cedarvale in the north” against “the upper middle class Humewood in the south” – they should have said ‘lower upper class’ in the north.

Now that you know, are you going to call this area The Woods? And will you call Forest Hill “The Forest”?

How do insiders refer to your neighbourhood?

Response by Daniel Rotsztain, the Urban Geographer

I love the notion of referring to it as “The Woods” and that being in the same category as “The Island” and “The Beaches”. It elevates this part of town by acknowledging its physical geography, it heightens my expectations for beauty in inland toronto, which is often dismissed as boring, flat, ugly.

You talk about scale: are the woods smaller than a forest? Is the Woods diminutive compared to Forest Hill’s perceived might?

The wikipedia article you referred me to groups together Cedarvale-Humewood so it makes sense that eglinton is the northern boundary… but I agree that the southern boundary doesn’t make sense, and as a natural feature and real “divide’, Davenport makes more sense.

You should try and edit the wiki! That’s the whole point of wikipedia right? Tho, they might not accept your edits because the description of the boundaries of the neighbournood is based on the City of Toronto’s official definition (there are apparently 140 official neighborhoods…) which is a silly exercise because we all have our own personal geographies and definitions of where a neighbourood starts and ends. I lived in Malmo, Sweden and it was much different: each neighborhood had a distinct boundary complete with a sign demarcating where one ended and the other began!

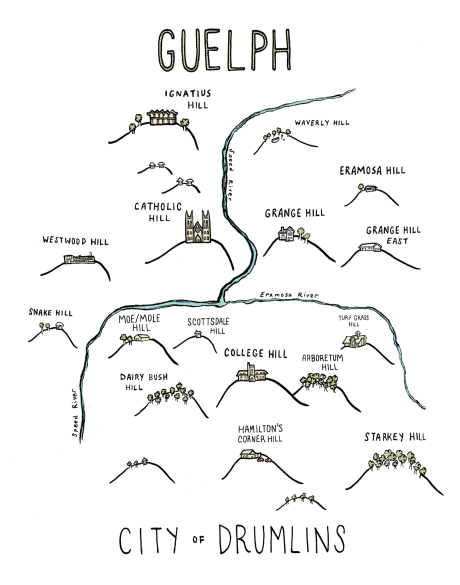

I will definitely start calling this area the Woods, thank you for this insider info. But I don’t think I will call Forest Hill, “The Forest”. It makes more sense to me to call it “The Hills”, linking it to the area west of it, which is all drumlins: egg shaped hills left over from the glaciers

Boardwalk on the way to Risser’s beach, South Shore, Nova Scotia

Boardwalk on the way to Risser’s beach, South Shore, Nova Scotia

Sherwood Forest in Toronto

Sherwood Forest in Toronto